Eric White, Nam!, 36" x 72", oil on canvas

Eric White, Nam!, 36" x 72", oil on canvasCurrent Issue Highlights More Readings DA Home About Direct Art

Art and War by Craig Stephens| "There are few die well

that die in a battle; for how can they charitably dispose of anything, when blood is their

argument," William Shakespeare-Henry V. |

Eric White, Nam!, 36" x 72", oil on canvas

Eric White, Nam!, 36" x 72", oil on canvas

As the reverberations of operation "Infinite Justice - The War On Terror, " and ensuing populist nationalism seep into the collective psyche, what effect is it having on the artists of America? How are they translating the rage, bloodlust and melancholia haunting the globe? War -- grotesque, evil and horrific is often perceived as something morbid, something unsavory, something to be shunned or feared. Is it wise for the artist to tackle such a theme when endeavoring to market their wares to an American public keen to decorate their living rooms and offices?

Perhaps the reaction of wider America, post September 11 can serve as a gauge. Various commercial radio networks exercised some bizarre censorship with one network issuing a ban on songs such as Don McLean’s "American Pie" and John Lennon’s "Imagine." Meanwhile, in the real world, two performances of the work of Karlheinz Stockhausen were cancelled in Germany after the avant-garde composer called the attacks "the greatest work of art for the whole cosmos." Alarmist behavior followed suite with The Empire State Building’s art gallery removing a 1945 photograph of a plane crashing into its facade.

Even for the chronically fickle, the events of Sept. 11 are hard to ignore. For some, it’s a shocked reaction to the apocalyptic visions of the WTC collapsing, for others it’s America’s bombastic nationalism, or even fear of future breaches to our civil liberties. Ultimately each trigger recounts familiar territory, synonymous with wartime throughout history.

Traditionally, art has prospered during wartime. From pre WWI, WWII, Vietnam, Korea, to the Gulf and Bosnia. Observing a few hallmarks of the last 100 years or so spans everything from Goya to Beuys and beyond. Capturing the terror, cruelty, and pathos of war, Goya’s "Desastres de la Guerra" cycle (etchings created between 1810 and 1816 and printed in 1892) was acknowledged as one of the first non heroic representations of battle.

About 150 years later, Joseph Beuys announced, "To make people free is the aim of art, therefore art for me is the science of freedom." As a German who shared the devastation and guilt of World War II, he was able to mine and transform his experiences, just as he transformed common materials into art. A perhaps apocryphal story was told of Beuys being rescued by Tartars and wrapped in felt and lard to keep warm during wartime service.

In Felt Suit (1970), a multiple of sewn felt, Beuys plays with the idea of felt as a protective, magical material. This felt suit is no ordinary suit, it is contemporary armor made out of humble cloth. An empty shell, without the human presence, it vibrates meaning and power, valid more as an idea rather than as an object. Beuys as a conceptual artist used nontraditional materials to call the tenets of traditional art into question. For him, art was not about beauty, but communication and freedom.

Fellow German artist, Helmut Herzfeld was contentiously acclaimed as the inventor of photomontage, having inspired everyone from Warhol to Robert Heineken. In the early forties he changed his name to John Heartfield as a deliberate protest when he heard about the anti-British WWI German slogan "Gotte Straffe England" [God punish England]. Heartfield was inspired in part by frontline German soldiers evading censors by clipping snapshots and photos sent with their letters home to compose what are regarded as the first photomontages. http://burn.ucsd.edu/heart.htm

For most Americans and Europeans, the Bosnian War, like the Gulf and Afghanistan was played out in the flickering images of television news. Yet another set of images, more permanent and profound, played an active role. Molding public sentiment and calling attention to the plight of the Bosnian people, for three hellish years, Bosnians plastered the walls of their towns with messages of anger, frustration, desperation, resistance, and hope.

Former Bosnian aid workers Daoud Sarhandi and Alina Boboc have since gathered over 180 of the most dramatic wartime posters, largely created by Bosnian artists and graphic designers at the height of the war. Fascinating on both political and artistic levels, they provide a harrowing account of the war and put a human face on this seemingly incomprehensible conflict.

Okay, so there’s some meaty insights into wartime art. For the writer, each begs the question, do periods of human suffering produce superior art?

EHREN TOOL

Gulf war veteran and LA artist Ehren Tool might confirm the theory. A specialist in ceramics and USC Fine Arts graduate, Ehren recently showed his first exhibition at LA’s Lord Mori Gallery in Chinatown, with a range of ceramics. Ehren’s bowls and cups are paradoxically embossed with bombs, guns and iconic war imagery, seemingly averting attention from the intentioned purpose of the object and highlighting the artists concerns.

Tool sent cups to various government officials including Vice President Chaney, President Bush, Colin Powell and even Charlton Heston. The work was displayed with a letter written to each and their subsequent response on departmental letterhead. "It has been an unreal experience seeing Humvees turn into Hummers with leather upholstery and CD players; to see camouflage meant to conceal you from someone trying to kill you turn into Camo skirts in Vogue, to see toy replicas of what was one of the most traumatic experiences of my life for sale at Toys "R" Us," says Tool.

"I do this work to deal with the things that disturb me. I especially like working in clay. Clay is not a precious material. It worked out that I could sell a photograph of one of my cups for about ten times the amount I’d sell a cup for. I figure the photo would last for about fifty years, while the cup would last 35,000 years.

"Since September 11, people I’ve spoken to have been more receptive to my work. It hasn’t changed, but the context in which it is viewed has. Once the yellow and ribbons and flags for this conflict have come down, there will be a group of eighteen to thirty somethings who will be forever changed. The conflict will end, but the actions they took, the things they have seen will not change."

Eric White,

Hats Off to Fission, 12" x 48", acrylic on wood

Eric White,

Hats Off to Fission, 12" x 48", acrylic on wood

ERIC WHITE

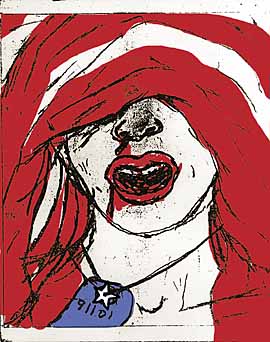

LA based Eric White is a 33 year old painter who explores the shifting boundaries between beauty and horror with surrealist fervor. A graduate of The Rhode Island School of Design, White’s work is rooted in photographic imagery, embossed with inorganic colors and virtuoso textures. His work isn’t photo realist in the context of being neatly mimetic; rather, he explores the formal qualities of photography and its capacity for distortion. Perhaps, as a result of their photographic leanings, the paintings are strikingly cold, devoid of emotion and charged with a sense of mechanized violence. With ‘Nam,’ one of White’s most profound works, he parodies the iconic photojournalism of Nick Ut and his highly recognizable Vietnam War photograph.

A fleeing Vietnamese girl is replaced with a contorted and naked Joan Crawford. 1940’s child movie stars run along side her in terror, while a Clark Gable figure has been cast in the role of the soldier in the background. The result is the surreal idea of a forties era war movie about Vietnam starring two of the studio’s heavy hitters in the lead roles. Adding to the complexity is the fact that the image appears to be burning, much like a movie that has been overplayed, disintegrating any notion of timelessness. "Though it makes blatant reference to the original photo by Nick Ut, the piece has very little to do with Vietnam," White confides. "Instead it serves as a sort of allegory. It’s about Western Culture’s diseased habit of romanticizing violence and terror, and vilifying sexuality (yet simultaneously relying on it as a marketing tactic). It’s about the glamorization of war by the corporate/State co-opted media and it’s failure to remain unbiased and truth-seeking".

"It also speaks of America’s whitewashing and exploitation of everyone and everything on earth. Hollywood seems as good a symbol as any to represent this notion; creating a synthetic reorganized reality and passing it off as the real deal. For me, the forties era is a much more aesthetically pleasing visual vocabulary to work with than contemporary Hollywood, plus it provides a sense of nostalgia. I also like the idea of a time warp; a forties movie about Vietnam. I’m exploring the idea that time is nonlinear and plastic". Mondrian said, "The position of the artist is humble. He is essentially a channel." This makes a lot of sense to me, because it often seems that ideas come in from somewhere else. Since I was a kid I’ve always wondered about what lies beyond our immediate awareness.

The idea that our perceptions, the five senses, are severely limited is fascinating to me. I’m really into metaphysics, specifically Jane Roberts’ work regarding the nature of reality. I’m also inspired by the dream state, which I believe is a reality as valid as this one, a place we travel to that actually exists, not merely random brain gas. I’m trying to create the sensation-disorientation, almost-reality of dreams in the paintings. They are sufficiently rendered to create a solid presence, and contain distortion and grotesque humor to bring them to the dream level, to "unreality."

Recently returned from Afghanistan, from what he describes as "an inspiring tour," LA based Robert Reynolds has a recurring fascination with war. Entwining personal allegory and historical references, Roberts work is both painting and sculpture based, often reinforced with multi dimensional usage of media and materials.

Marilyn at Auschwitz, serves as a metaphor for the controversial and even precocious nature of Reynolds’ work. The oil painting with neon sign attachment sees a cell lined with double bunks occupied by emaciated Jewish refuges. The uniformed men stare blankly, while Hollywood icon Marilyn Monroe stands in the middle of their cell in all her skirt raised glory.

Reynolds says his work is a reaction to war, consumer society and classification systems, where ideas of protection and defensiveness from the outside world are reassessed."War is something that is still inherent in the human psyche, something that we still haven’t evolved from. I’ve also had first hand experience with war, I have friends who are both veterans and war correspondents and I’ve always been mesmerized by their fantastic tales," he says.

"When specifically observing the current situation in Afghanistan, I don’t actually agree with the bombing of peasants, yet they suffer as the Taliban were out to kill us. I do think it’s a reaction to the US foreign policy, though Americans have endured a lifetime of propaganda, which have instilled many misconceptions about the Arab world, I can recall watching Walt Disney cartoons in which Arab were always stereotyped as sinister dangerous and untrustworthy".

Roberts confesses a fascination with adopting a perspective of either the attacker or attacked. His series, Faded Memories Of History reference battle via sunken warships, while Untitled Six, a painterly portrayal of one of the last photographs taken of a group of Kamikaze pilots sees a sense of irony through movement and time, linking nature, process and memory. A more recent, as yet incomplete series aims to emulate the view from an aircraft cockpit as it flies towards an NYC skyline.

"Apart from being tempted by the offer of $25 million for Bin Laden, I found that on a lateral level, traveling anywhere always helps with any sort of creative block. Yet I do feel compelled to draw some conclusions from the scenario, and find it ironic that America is spending billions everyday to maintain a military presence in Afghanistan, while the attack on the WTC costing within the vicinity of a million managed to cause so much damage."

"Ultimately, I think terrorism is born from frustration, when no other forum to voice an opinion is available. The attack was spawned by our relationship with Israel and our lack of objectivity, the US also inspires a lot of jealousy, envy and hatred from other nations, whereas races such as Palestinians have spent their whole lives in concentration camps".

Jordon Isip, Natal, 19.5" x 25", mixed media

Jordon Isip, Natal, 19.5" x 25", mixed media

JORDIN ISIP

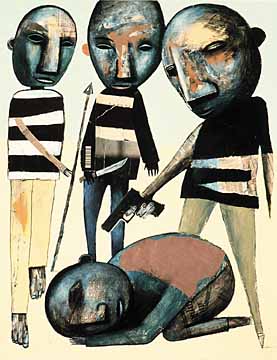

Jordin Isip was born and raised in Queens, New York. Since receiving a BFA from Rhode Island School of Design he has resided there. Isip’s naive drawing style serves to paradoxically reinforce the seriousness of his subject matter, exemplified by paintings such as, The Warlords Of Natal and Cause and Defect. Expressionistic and emotional, the works embody muted, earthy tones, layering patches of color in smooth strokes with a painterly sensibility. Isip’s war paintings approximate psychological and emotional turmoil. They reflect fear and confusion through symbolism that captures varying levels of perception, blurring the boundaries between beauty and horror. The almost metaphorical figures are soulful, with swollen heads and big, expressive eyes, while ensuing thematics tackle desensitization to psychological terror and man’s lost compassion.

Islip’s mixed-media images have also appeared in numerous periodicals, and he received assorted awards for his work, from and publication in annuals including American Illustration, The Art Directors Club, Communication Arts, Print Magazine, and The Society of Publication Designers. In addition, he has shown his work in solo and group exhibitions in Los Angeles, New York, Philadelphia, San Francisco, Ontario, and Rome. "I do not see the terrorist act or the collapse of the WTC itself as art, " he says. "Though I did feel conflicted when I saw the second tower get hit by the airplane. As my mind was trying to figure out what exactly it was I witnessed, I could see the broken glass shimmering in the sunny blue sky slowly floating downwards. It looked beautiful, but knowing where it had come from made me sick".

"I was finishing up a commissioned piece that day and I was working on the sky so I painted it as it appeared out my window here in Brooklyn, which was beautiful, sunny, crisp and blue with a dark dagger of a smoke coming right over our neighborhood, splitting the sky in half. Afterwards I couldn’t do anything, I didn’t want to make art, or think about art. I was depressed, angry, sad and scared. People I knew were missing. Witnessing a grand atrocity like that was confusing. I felt a visceral sickness and conflicting emotions and thoughts were racing around my head. I could not make sense of it.

"With time passing it is still incomprehensible, but it will probably enter my artwork. I think more social or political art is created during wartime because people’s lives are affected more directly. People need to talk about it, express themselves, and speak through their art".

What art has impressed him throughout history? Picasso’s "Guernica," and Goya’s "The Disasters of War" immediately come to mind. Other artists that have madepowerful visual art about war that I think of are George Grosz, John Hearfield, Leon Golub, Kienholz, Brueghel, Durer, Sue Coe, Daumier, Frans Masereel and Ben Shahn.

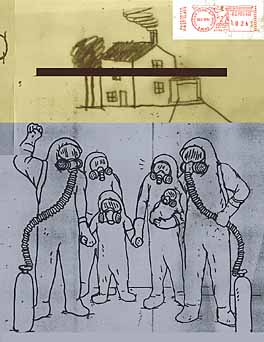

JONATHON ROSEN

The work of Jonathan Rosen tackles a spectrum of themes and issues, from mundane human experience, through to religion, and spirituality, erotica, and industrialization. Highly sensitive, Rosen presents a big focus on eclecticism, inherent of his broad experience and training as an artist.

Stylistically the work is distinct. An historic comic book style is melded with a traditional etching technique, that manages to create a dirty realist quality, unspooling psychological dysfunction and in turn drilling holes through the tight perimeter of perceived reality. Rosen moves away from being literal and ironic, and into more ambiguous territory, sifting through his emotional architecture into other realms of consciousness.

Now NYC based, Jonathon Rosen spent six years at various city and state colleges in the LA area studying electronic music, printmaking, painting and color-separation. He spent a further seven years as fine art editions printmaker for several master printers in LA, specializing in Intaglio/lithography/woodcut/serigraphy.

Jonathon Rosen,

Hazmat Family, digital media

Jonathon Rosen,

Hazmat Family, digital media

Rosen’s career has since evolved to the point where he has published his own book of work, Intestinal Fortitude (1990 by Poote press, New York) and a limited edition letterpress book of drawings. He has also won a host of awards, including Best illustration (gold) 1995 by Society of Publication Designers 1999 Artist-in-residence award at Harvestworks, and admits to an admirable obsession to playing the process electric saw as a musical instrument. Of wartime art, Rosen says that while art is usually effected adversely during wartime, he has sought inspiration from the likes of Dr. Suess, Goya, Brueghel, The Thin Red Line, and Trajan’s Column, Rome. Asked how he felt about the comment by Karlheinz Stockhausen, that the collapse of the WTC was "the greatest artwork ever" Rosen confides, " he was actually referring to the scale and effect of the terrorist’s work compared to the powerlessness of the modern composer to affect society the same way. He was jealous, in other words, -- though the comment was idiotic."

Was he inspired by the event to create art ? "Yes, but only in response to all the insipid soulless art made by graphic designers about the tragedy. Art does have a role in politics in that every person in power needs a scapegoat and a jester."

HECTOR VELEZ

Hector Velez sees his art as a preoccupation with the depiction of highly charged, personal internalized visions, a place where abstraction and representation coexist in a dense forest of the subconscious, a receptacle where intense stories are told.

Having studied architecture in Mexico and Fine Arts in Spain, Velez sees his cultural background and studies as equipping him with the tools to create art. "My first contacts with art were during my teenage years. I was heavily influenced by religious paintings of colonial times and the muralist movement in Mexico."

"The Renaissance period was the most influential on me in terms of wartime art. This is not only due to its importance as an art movement, but because we are seeming to be revisiting the same aesthetics of that time, with the world now as Gothic as it was back in the 15th century."

Velez chose two key paintings to represent his stance on war and the artworld. The enigmatically titled Flag selects uncharacteristic objects and groups them to recall the color and shape of patriotism, a seemingly insignificant note also enters the frame, serving as an understated reminder of apocalyptic visions. Another oil on canvas work, Good and Evil depicts two high caliber bullets, underscoring the futility of war, offering both sides equal footing via generic anonymity, veiling any bias or favoritism.

"I don’t agree with the notion that the WTC collapse was an artwork in itself," Velez says. "Where is the art in the slaughter of thousands of people? I wasn’t necessarily inspired by the event, more compelled to create, as I see art as a vehicle to vent my feelings. It’s more about trying to grasp the everlasting pain of those closer to the catastrophe."

"To some extent, art in times of war becomes a tool of propaganda for or against the conflict of both sides. I think art must have a role in politics, especially if you consider that the politics of that world change constantly, shaping the times of the society, and when that civilization is gone or changed, the only record of its existence is the culture that survives it."

Current Issue Highlights More Readings DA Home About Direct Art